Core Concepts

The Boxed approach takes root in typed functional paradigms. We know that these concepts can be overwhelming, especially with their jargon and mathematical concepts, and therefore want to make them more accessible.

As beautiful and powerful these concepts are, they come with a huge learning curve that we want to avoid. We also want your code to be simple to read, write and reason about without having to know the full theory behind.

If you have a strong opinion on what metaphor to use to describe monads, please stop reading this page immediately and visit the API reference.

Schrödinger's cat

When physicists discovered that particules do weird stuff, they decided that while we don't look at them, they're in a superposition of states.

Erwin Schrödinger didn't like that one bit and decided to show them how utterly stupid it was. For that, he created a thought experiment now called the Schrödinger's cat experiment, in which a cat is put into a box (roll credits) with a cat-killing device reacting to some quantum stuff. While we don't open the box, the cat is both alive and dead as the same time, when we open the box, we fix an outcome.

We love cats and the boxes used in the following explanations will only contain JavaScript values.

Boxes

The way we like to think of the data-structures we expose are that they're boxes (think of it as containers) that may or may not contain a value.

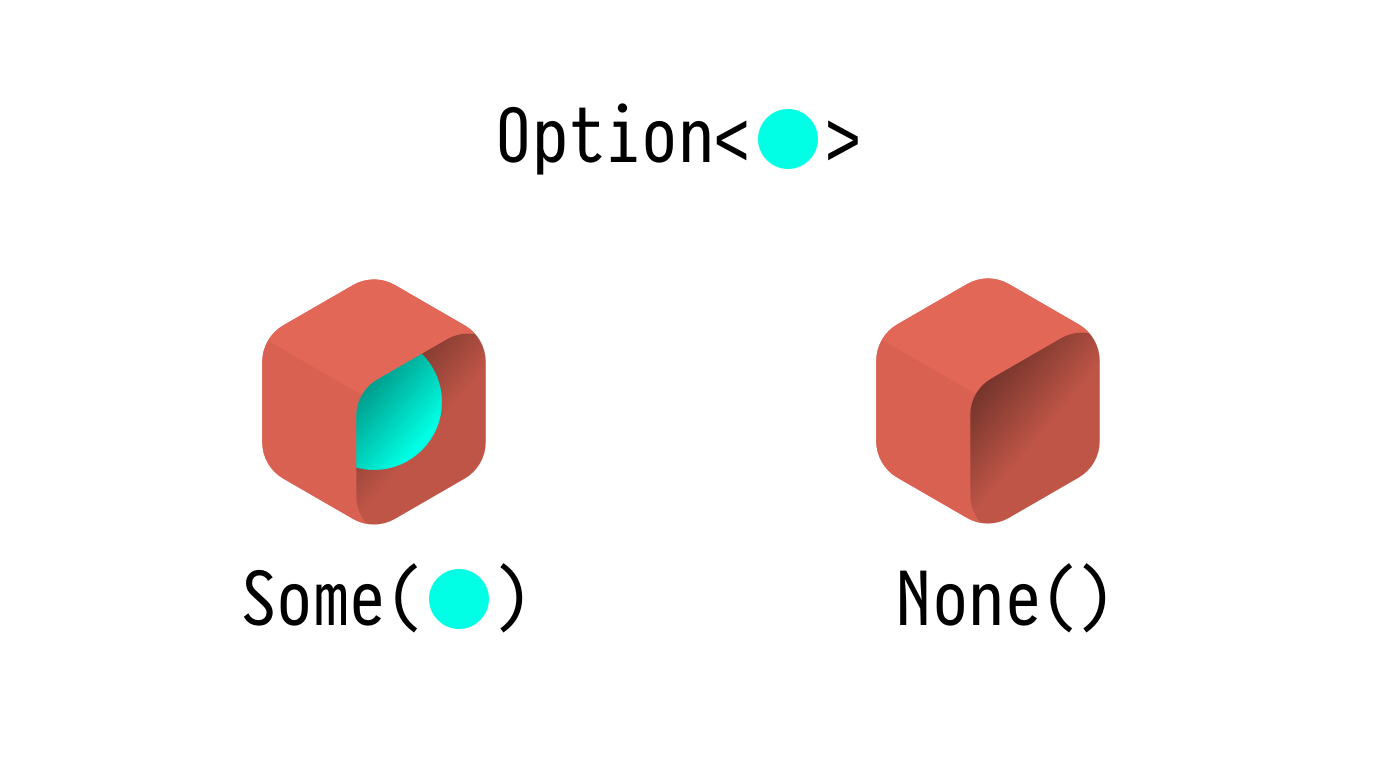

Here's a visual example using the Option type. The Option represents an optional value, it can have two possible states: either Some(value) or None().

Option is a generic type, meaning you can define what type of value it holds: Option<User>, Option<string> (just like an array: Array<User>, Array<string>).

In your program flow, you don't know what's inside, as if the box was closed.

When you extract the value from the box, you have a few options:

// Let's assument we have `option` be of type `Option<number>`

// Returns the value if present or the fallback otherwise

const a = option.getOr(0);

// Explode the box

const b = option.match({

Some: (value) => value,

None: () => 0,

});

Data-manipulation basics

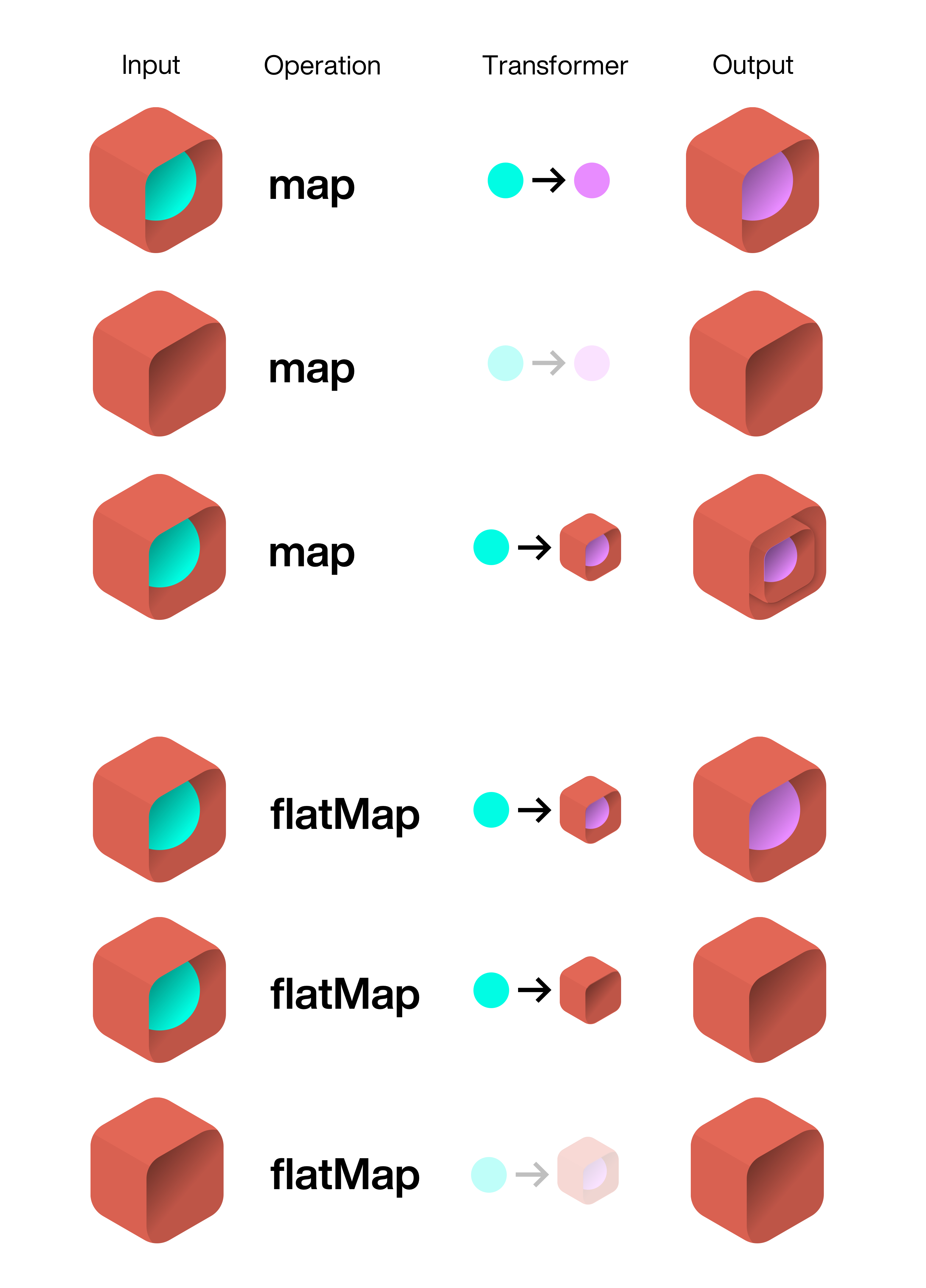

Most of the data-manipulation you'll do comes down to two function: map and flatMap.

Here's a visual explanation:

The map and flatMap functions allow you to transform data in a typesafe way:

const some = Option.Some(1);

// Option.Some<1>

const none = Option.None();

// Option.None

const doubledSome = some.map((x) => x * 2);

// Option.Some<2>

const doubledNone = none.map((x) => x * 2);

// Option.None -> Nothing to transform!

The flatMap lets you return another option, which can be useful for nested optional values:

type UserInfo = {

name: Option<string>;

};

type User = {

id: string;

info: Option<UserInfo>;

};

const name = user

.flatMap((user) => user.info) // Returns the Option<UserInfo>

.flatMap((info) => info.name) // Returns the Option<string>

.getOr("Anonymous user");

The main kind of boxes

Option<Value>

Represents optional values:

- Replaces

undefinedandnull - Makes it possible to differentiate nested optionality (

Some(None())vsNone()) - Reduces the number of codepaths needed to read and transform such values

Result<Ok, Error>

Represents a computation that can either succeed or fail:

- Replaces exceptions

- Allows you to have a single codepath instead or "return or throw".

- Makes it easy to aggregate all possible errors a stack can generate

AsyncData<Value>

Represents a value with an asynchronous lifecycle:

- Eliminates impossibles cases in your state

- Avoids inconsistent states induced by traditional modeling

- Allows you to tie the lifecycle information with the value itself

Future<Value>

Represents an asynchronous value:

- Replaces promises

- Supports cancellation

- Delegates success/failure to the Result type

- Exposes a

map&flatMapAPI